Two smooth branches nailed into the shape of a cross adorn the trunk of a scraggly maple tree below a photograph of 20-year-old Rebecca Ryan. The makeshift memorial at the popular rock-climbing destination known as Lower West Bolton is a reminder that Ryan and her easygoing smile will never return.

She died in a fall at the rugged 90-foot wall of rock in Bolton on September 16, as two friends waited below.

The loss of the University of Vermont junior devastated fellow students and her family. It's also triggered conversations about safety in relation to a sport that is growing in popularity with adrenalin junkies around Vermont.

Ryan fit the climber profile. The young woman skied alpine race courses at 40 miles an hour, kayaked in waters off Alaska and picked her way over ice-covered glaciers. She'd been climbing for at least two years and had even checked out the competitive circuit.

The Vermont State Police say they have not completed the final report on Ryan's accident and denied a public records request from Seven Days for the document last week. The preliminary one, penned by Vermont Department of Public Safety search and rescue coordinator Neil Van Dyke, was posted at climbing resource website neclimbs.com in response to climbers who were calling for more details about the accident. His account did not name the two climbers who were with Ryan, and Van Dyke, a veteran ice climber, also declined to identify them to Seven Days.

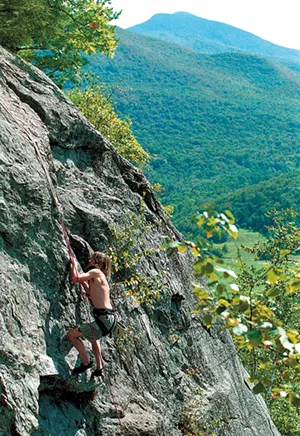

UVM has a rock-climbing club, but this excursion was just an outing among friends. Ryan and her companions had headed to Lower West to tackle a popular climb. A half hour from Burlington, it's an easy walk from a parking pull-off on Bolton Notch Road. Seven Days visited the site last week with Seth Maciejowski, an avid climber who serves as president of CRAG-VT. The nonprofit group, based in Richmond, promotes safe climbing and works to preserve and expand access to climbing areas in Vermont.

Signs at the start of the path mark the area, including one that warns: "Rock climbing is dangerous. Climb at your own risk!" Another notes that CRAG owns Lower West and urges visitors to join the group. CRAG has about 150 members statewide.

The sun filtered through the birch, beech and maple trees en route to the base of ancient cliffs. Autumn leaves helicoptered to the ground alongside the walls of schist — a gray, coarse-grained rock — that form a buttress 90 to 120 feet high.

Nobody was scaling the cliff that day, but evidence of its popularity was everywhere. The slippery lichen known as rock tripe had been scrubbed clean along the well-traveled vertical routes. Here and there, white marks indicated spots where climbers covered their hands in chalk to better grip the crags. Numerous steel bolts screwed into the rock provide more reliable protection.

Ryan and her climbing partners were not using those permanent bolts that day on their route, known as Harvest Moon. Instead, they were "top-roping" — a technique that involves looping the rope around a tree or through a secure anchor at the apex of the cliff. One end is secured to a harnessed belayer on the ground; the other is attached to the climber above. The belayer keeps the rope taut as the climber ascends, to prevent a fall.

Climbers can lower themselves in the top-roping scenario, too, with the belayer providing a counterweight and slowly giving the climber more rope to descend.

The trio made several climbs and were ready to leave, according to the preliminary report. Ryan ascended one more time to collect equipment at the top, where the rope was anchored onto two rings bolted into a boulder.

In the report, Van Dyke refers to Ryan as "climber #1." Her climbing partners, referred to as "climber #2" and "climber #3," believed the plan was for "#1 to ascend, clean the anchor and rappel down." Cleaning anchor entails resetting the rope at the top, so that all gear can be collected and ropes pulled down from the ground after a final descent.

Rappelling would have involved Ryan threading the rope through a piece of gear and lowering herself from the top anchor — without the assistance of a belayer below.

According to the report, Ryan climbed up and called "Off belay," signaling to her partner on the ground to remove belay equipment from the rope, presumably so she could rearrange the roping and "clean anchor." The belayer took off the harness, believing that Ryan would rappel down without help. Then things got confusing, according to the report.

"About 5 minutes later #1 called, 'Are you ready to lower?' Both #2 and #3 shouted 'no' back, and #2 rushed to put their harness back on. Less than a minute later Climber #1 was observed in an uncontrolled fall down the face, which she did not survive."

Ryan did not have a rappel device on her harness. It was found in a pile of gear at the base of the climb, according to the report.

Van Dyke concluded that the "most likely scenario" was that Ryan had intended to rappel down but realized she had left that crucial piece of equipment behind. She probably didn't hear the "no" shouts from below and leaned back to descend, expecting to be lowered, and fell. But it's also possible that she slipped, his report says. There's no way to know for sure.

Her loss hit Vermont climbers hard. They're weighing in on online chat boards, paying their respects, attempting to analyze the emerging details and also reflecting on the dangers of the sport. Some climbers have offered their own close-call tales.

Rock-climbing deaths are rare but not unheard of in Vermont. Two years ago, in 2015, a Sunderland rock climber fell to his death in Dorset as a result of a rappelling error. There have also been fatalities and serious accidents at Smugglers' Notch, news stories and accident reports show. Some are tricky to categorize. For example, in 1980, a man died after a 30-foot fall while climbing at the Notch without any ropes or gear — an incident Van Dyke considers a hiking death not a climbing one. Vermont State Police do not keep a tally of rock-climbing fatalities.

For all the technical gear that climbers use, from carabiners to harnesses, one of the most important tools is communication, Maciejowski emphasized.

It's "imperative" that your partners "know exactly what you are doing," he said.

When in doubt? Walk down. Some commenters noted that's what Ryan should have done if she couldn't hear her partners. At West Bolton it's an easy 12-minute hike from the top of the cliff to the base.

Despite the dangers, more and more people are negotiating rock faces. Indoor climbing gyms and mini-walls at playgrounds and resorts are proliferating — and leading newcomers to the sport to then venture outside.

Twenty years ago, the cliffs at Bolton had just a few marked routes, said Maciejowski. Now, there are probably 200, he said. Students from Middlebury College, Saint Michael's College and UVM climb there.

And there are plenty of other spots, too. CRAG owns 58 acres at four cliff bands in Vermont and is raising funds to buy property near Lower West known as the Bolton Dome. The nonprofit is negotiating with the Episcopal Diocese of Vermont for permission to climb at Rock Point, the limestone cliff in Burlington overlooking Lake Champlain. CRAG members are also working with state officials on getting signs to mark a popular route for bouldering — climbing huge rocks without ropes — at Smugglers' Notch. So far, most of the group's minimal funding has come from memberships, donations and grants.

The sport draws thrill seekers such as Ryan. She'd always been game to conquer whatever challenges the mountains offered, recalled her father, Ron Ryan, a consultant and entrepreneur who lives in Knoxville, Tenn.

When Rebecca Ryan was a child, the family lived in Missoula, Mont. The little girl learned to ski steep faces and bowls that left her own mother, Martha, quaking at the top, Ron Ryan said.

Their daughter started alpine racing in Montana and continued training after she, her two siblings and her parents moved to Tennessee. She enrolled at the Green Mountain Valley School, a ski academy and boarding school in Waitsfield, and thrived there during her teen years. A crash at Sugarloaf in Maine slowed her down.

"She fell on the headwall. Her leg was twisted around behind her head, and she broke her femur pretty cleanly," her father recalled. A surgeon put Rebecca Ryan back together, but she had lingering problems.

"She competed the next year, her senior year, but she was under tremendous pain and really didn't ski terribly well," he said.

So Ryan found other outlets. At UVM, she enjoyed hiking, camping and teaching people with disabilities how to ski. A practicing Presbyterian, she found a deeper spirituality in the UVM InterVarsity Christian Fellowship. She spent her spring breaks on mission trips with the campus group.

"It was something much more powerful than someone who gets up and polishes their shoes and goes to church every Sunday," her father said. "It was something she was much more committed to than that.''

He declined to discuss any details of the accident, saying it was too difficult.

"I think that one of the most important things that gives us as parents comfort is that she lived an extraordinary life," he said. "It was short, but it was very beautiful."

He and his wife sometimes talked to their daughter about the wisdom of her athletic pursuits, especially after a fall during an indoor climbing competition caused a second major injury during her first year at college. The compound fracture to her right ankle required surgery and more rehab.

Still, Ryan recovered and made inspirational posters to help with the journey. One of them, her father remembered, summed up her attitude well. It quoted a line from a Harry Potter book that said: "What's life without a little risk?"

No comments:

Post a Comment